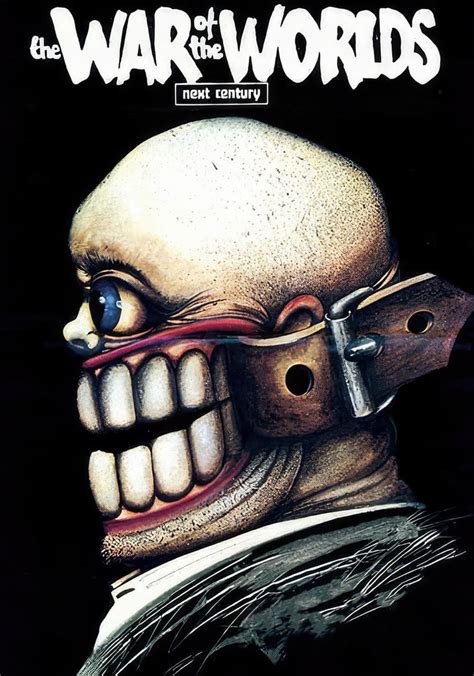

A few days ago I saw a post titled “Soviet versions of popular film posters” and they claimed that the below image was the Soviet poster for 1953’s War of the Worlds.

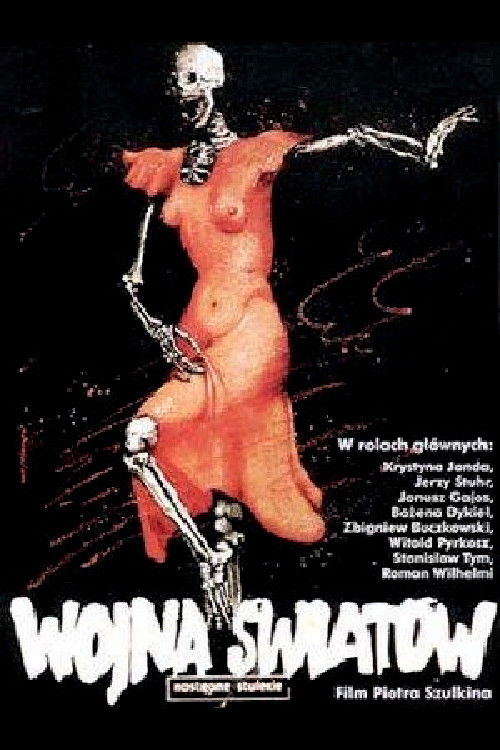

Looking at this somewhat bizarre face one might be confused as to why this was the poster design for the 1953 sci-fi film; and that’s because it’s not the poster for that film at all. It’s the poster for Piotr Szulkin’s 1981 Polish film The War of the Worlds: Next Century, or Wojna światów - następne stulecii, by Andrzej Pągowski. In fact this poster’s artwork isn’t even the original Polish language version; the English title makes it much more likely that this is the promo for the foreign release. The Polish version (also by Andrzej Pągowski) looked like this:

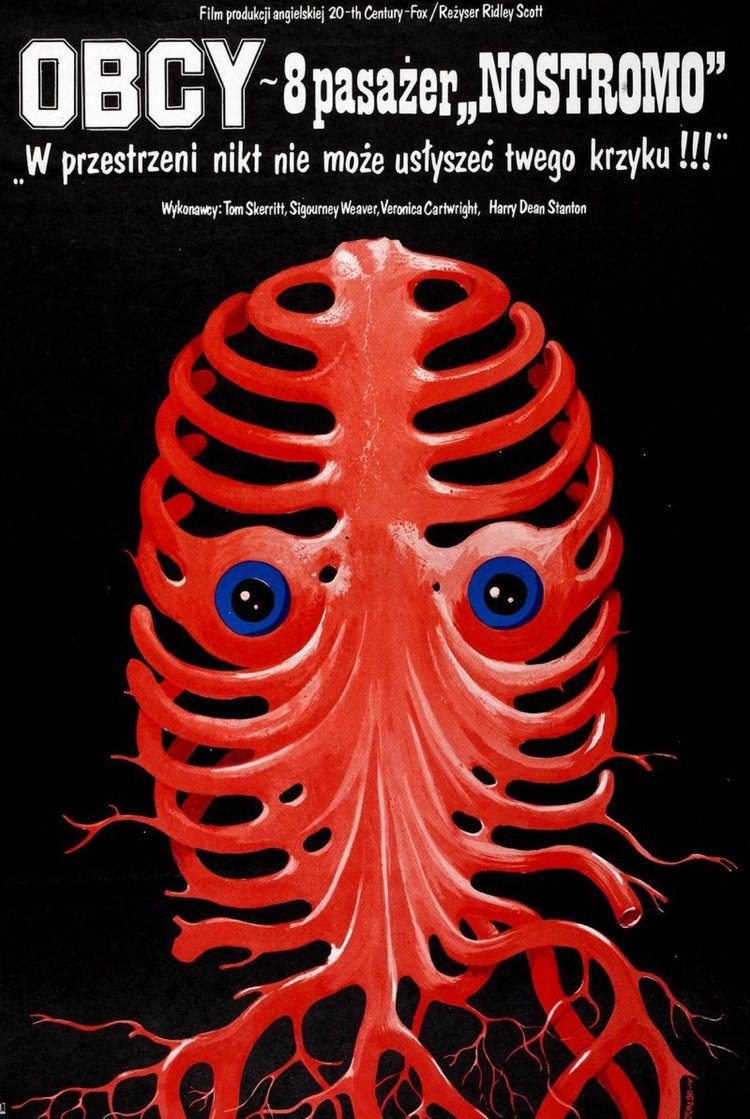

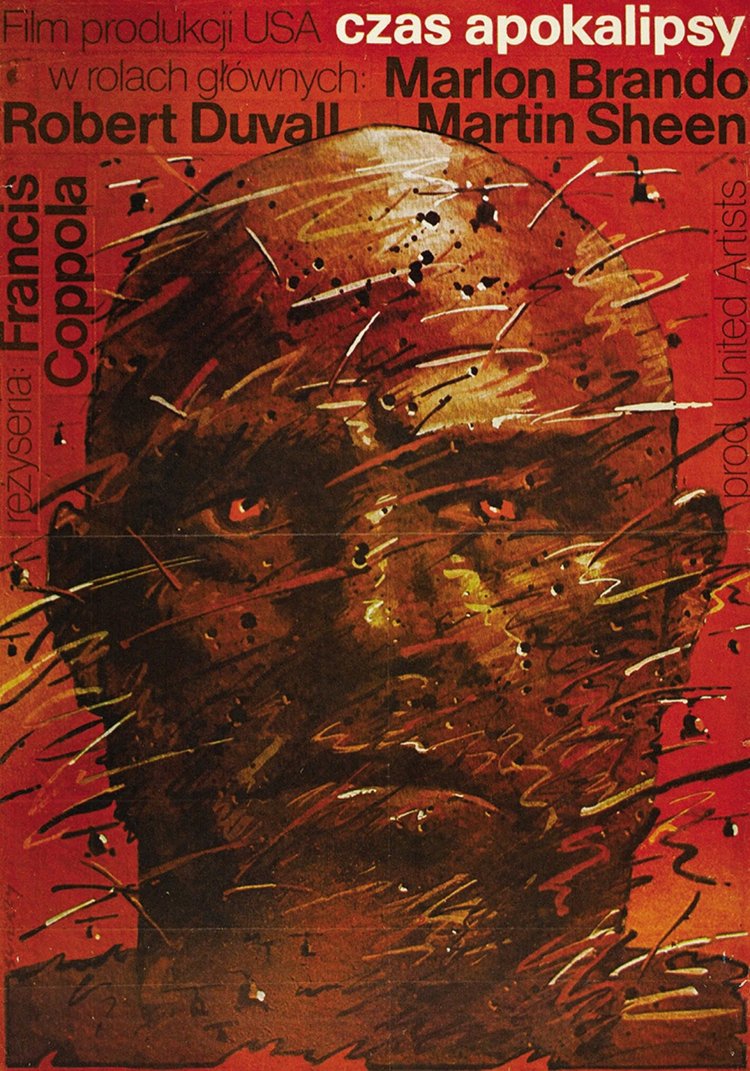

I’m being quite specific by calling these Polish posters rather than Soviet, as the other posters the post shared were all specifically polish too, but properly identified as to what film they were for:

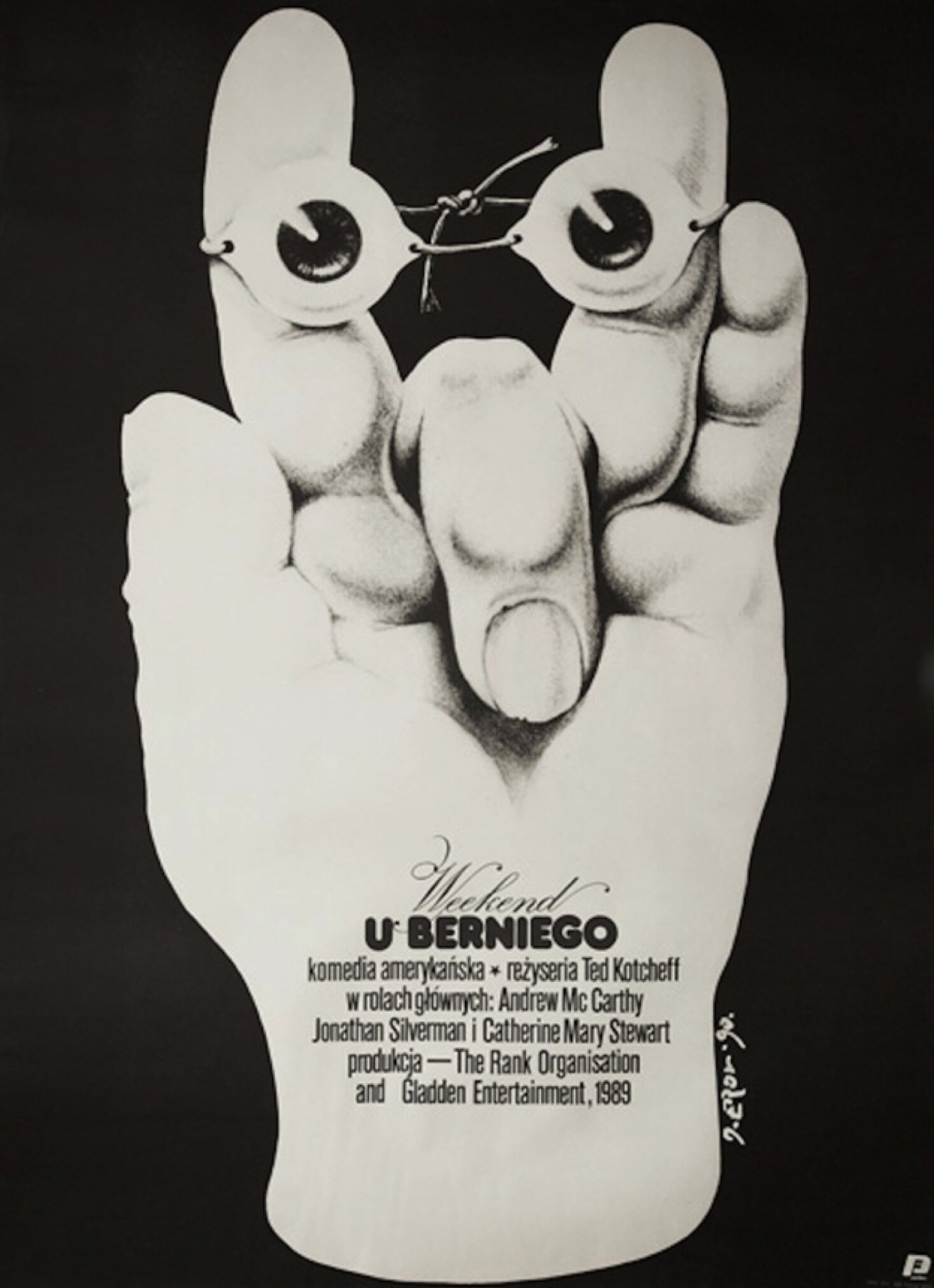

First and Last: Alien (1979), and Weekend at Bernie’s (1989) by Jakub Erol. Middle: Apocalypse Now (1979) by Waldemar Swierzy.

The reason I’m being so specific about their Polish origins, is that these were not what film posters looked like across the USSR and it’s satellite states - these are very much unique to Poland, and to the Polish School of Posters.

At the end of the 19th century, Poland was divided amongst Russia, Austria and Prussia. In Kraków, the Młoda Polska movement, comprising of artists of various mediums, worked to revitalise Polish art, and preserve the national culture and identity with a modernistic approach - preserving the Polish identity even when the maps of the day had nowhere by that name. Like many in Europe, these artists were inspired by the dazzling French chromolithography of Jules Chéret - whose work became what we know as the modern poster. It soon became the preferred medium to express their artistic aims, and when Poland gained it’s independence in 1918, there was a mixture of influences that all contributed to the continued development of the poster in Poland. Rapid industrialization, tourism, and new trade networks demanded posters-as-advertisements, while socialist influences inspired the style of social realism amongst artists, connecting the Młoda Polska’s interest in their nation’s folk art with the community-driven, drive to honor the workers and peasants.

After the devastation of the Second World War, Poland, now a Soviet satellite state, introduced a strict style of Socialist Realism for any state sponsored posters - which was now the only way a poster could be produced. Artists were therefore unable to make money through other styles, and were economically restricted from expression. However, they were highly sought after; giving them the difficult task of reconciling their artistic aims with the reality of the state’s needs. Despite this conflict of purpose, and how some commentators wax poetic about the dreary life of Communist rule; there was a lot of hope and excitement in artistic circles, especially in architecture; there was a sense that the rebuilding of cities such as Warsaw, were a blank slate for new and different designers. Even before the ‘Polish Thaw’, and the end of Poland’s adherence to Stalinist Socialist Realism, the state shared their excitement and founded the Office for the Supervision of Aesthetic Production without any political or ideological aims, instead focusing on the profession of aesthetic design and production. Even the panels of censors that are often cited by those writing on this topic, are misrepresentations of reality; the panels were in fact manned by the artist’s peers, and their job was not to censor, but assure the quality of the work. This was especially important, given that the posters of Poland were a source of pride for the Soviet union, and something revered internationally.

The 1950s and 60s are often seen as the golden age of Polish poster art. During this time both Film Polski and Centrala Wynajmu Filmow (Movie Rentals Central or CWF) commissioned artists rather than graphic designers to produce posters for film releases. In the mid 1950s, after the ‘Polish Thaw’ and the lifting of stylistic expectations, the field blossomed; with artists working outside of commercial constraints, there was no need to juggle profits and ticket sales along artistic expression. The poster was artist-driven, with complete disregard for the demands of the film studios. Posters became personal and deductive, interpretive and freely expressive.

Some bemoan the following decades of the 1970s and 80s as a great decline of the Polish poster - but I myself love the works of this period as much as those prior. I’m not alone, either, as the post that inspired me to write this shows - thanks mostly to the nostalgia for the cinema of the two decades, I’m sure.

In 1989, when film distribution was privatized, and state sponsorships ended - the poster hegemonised with the west, and with the marketing world now in charge of their design and distribution, there was no space for the public art of the Polish poster. Even those who try and continue the legacy create limited runs, hidden in galleries and far from the streets they once decorated.

Not a lot have people have seen The War of the Worlds: Next Century compared to the 1953 American film, so I bemoan no one from outside of 1980s Poland for not recognising the poster. In fact even the Vinegar Syndrome 2-disc Blu-ray collection of Piotr Szulkin’s apocalyptic films doesn’t have this artwork anywhere on the cover. Originally all I wanted to do was write a quick correction, a little tid-bit about a lesser-known film, but I thought a bit of history might be a bit more interesting.

Edit Thu 22 Jan: Although the Vinegar Syndrome release that included War of The Worlds: Next Century did not have the Andrzej Pągowski artwork, the Radience limited edition does.

Bibliography

- Austoni, A. (2010). The Legacy Of Polish Posters. [online] Smashing Magazine. Available at: https://www.smashingmagazine.com/2010/01/the-legacy-of-polish-poster-design/ [Accessed 12 Jan. 2026].

- Boczar, D.A. (1984). The Polish Poster. Art Journal, 44(1), pp.16–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00043249.1984.10792515.

- Crowley, D. (1994). Building the World Anew: Design in Stalinist and Post-Stalinist Poland. Journal of Design History, 7(3), pp.187–203. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/7.3.187.

- Czestochowski, J.S., Fijałkowska, J. and Muzeum Plakatu W Wilanowie (1979). Contemporary Polish posters in full color. New York: Dover Publications.

- Kuznar, T. (2025). Classic Polish Film Posters. [online] Cinemaposter.com. Available at: http://www.cinemaposter.com/ [Accessed 12 Jan. 2026].

- Schneider, F. (2015). Reflecting the Soul of a Nation: Polish Poster Art - Illustration History. [online] www.illustrationhistory.org. Available at: https://www.illustrationhistory.org/essays/reflecting-the-soul-of-a-nation-polish-poster-art [Accessed 11 Jan. 2026].

- Sedia, G. (2021). Polish Film Posters. [online] Kino Mania. Available at: https://kino-mania.net/polish-film-posters [Accessed 11 Jan. 2026].